By Dr. Robert Gudmestad

“I teach history; they were history,” said Dr. Mike Mansfield, an instructor in the Department of History, as he introduced 96 year-old Leila Morrison and 85 year-old Win Schendel. On November 14, 2018 Morrison and Schendel spoke about their experiences in World War II. Landon Schmidt, a CSU student who is active in veterans’ causes, helped Dr. Mansfield organize the event, which attracted a crowd of nearly 400 people.

Forced into the Hitler Youth

Schendel explained that he received a dagger when he was forced into the Hitler Youth and learned how to fight. He related how, in one exercise, all the boys received armbands and they were supposed to tear the armband off of the other boys. Anyone who lost his armband was “dead.” Schendel also competed in a game where the boys in his unit had to take a flag from the local castle. He said that most people did not understand what was happening in Germany at the time and were not involved in political discussions. His father, though, disagreed with Adolf Hitler’s policies and the Gestapo “beat the hell out of him several times” before killing him. A couple of years after his father’s death, Schendel and his mother were in Bayreuth, Germany, when Hitler’s car stopped and Der Fuhrer emerged. Schendel went over and shook Hitler’s hand. “I still remember looking at him…I still remember that look,” Schendel recalled. He thought it was the look of pain.

A US Army Air Corps Nurse

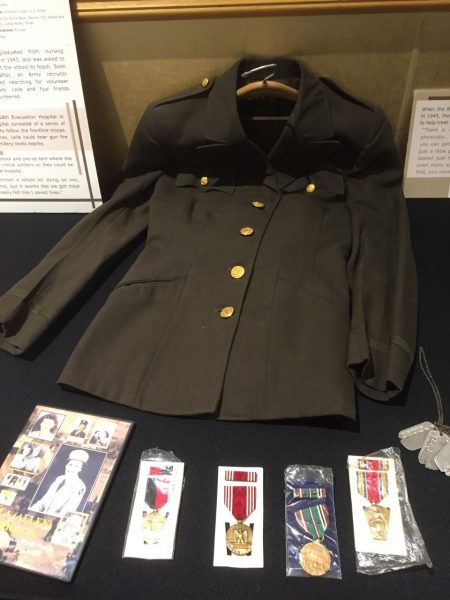

Morrison, who grew up in Blue Ridge, Georgia, noted that, “I was born to be a nurse.” She was twenty-two when she enlisted in the United States Army Air Corps, the forerunner of the Air Force. She underwent basic training in Colorado and then experienced overseas training in Texas. One night she got word from her commanding officer to “be ready in the morning. We’ll be shipping out.” Morrison and her fellow nurses were relieved when the train headed east as they thought service in the European Theater would be better than being stationed in the Pacific Theater. She traveled to England on the Queen Elizabeth, the famous ocean liner that had been converted into a transport vessel. The conditions were hardly luxurious, though. She stayed with eight other nurses in a room that normally held one person. Once she arrived in England, Morrison enjoyed meeting local citizens and told a story about a young boy who asked her if she was a “Yank.” In her distinctive southern drawl, Morrison quipped that, “I thought, oh, I’m from Georgia. What am I going to say?” She reluctantly said yes, much to the amusement of her friends. “I never lived it down,” she chuckled.

In 1944 Morrison landed at Normandy Beach. “It was a very emotional time…I felt it was almost sacred ground,” she said. Almost immediately she joined a field hospital as a pre-op nurse. Morrison described the hospital as a bunch of tents that followed the front as it advanced. She was in the pre-op tent where she tried to prevent soldiers from hemorrhaging and keep them from going into shock so that the doctor could operate. Conditions in France were adequate, but it was so cold at the Battle of the Bulge, Morrison remembered, that American soldiers lost arms and legs to frostbite. She treated soldiers in both armies and could not believe the state of the German army; Americans were fighting against little boys and old men, Morrison recalled.

Refugees and Survivors

As the Allied armies advanced closer to Germany, Schendel also felt the effects of the war. He and fellow members of the Hitler Youth had to scrounge for spent shells from aircraft raids, re-stock rooftop arsenals, and dig through the rubble to find bodies. “I saw more people dead than I ever want to see again,” he noted sadly. Schendel lived with his mother in a four-story apartment building where they kept tubs of water and blankets on hand in case the fires became too intense. The bombing was severe: Schendel explained that the bombs sounded like freight trains and he experienced hearing loss from the tremendous pummeling the Allies inflicted. He and mother became refugees because their building was severely damaged. By this time Schendel knew the war would be over soon because he could see the lights from the Allied lines grow closer every evening. Then, one Sunday, the American tanks appeared. “I’ve never seen so many tanks in my life,” Schendel said. Although he was happy to surrender and said that the Americans treated very well, he wistfully recalled how his thirteen year-old friend bled to death in the final days of the war.

Morrison, meanwhile, was always confident that America would triumph. “I knew we were going to win the war because we were a Christian nation,” she said. After the surrender, she visited Buchenwald concentration camp, the largest such facility in Germany. A man who survived the camp by pretending he was dead gave her a tour of Buchenwald. “The things that he showed us changed my life,” Morrison said sadly. In the crematorium, she saw sixteen ovens and a “whole wall” of glass jars that contained human ashes. She also met survivors of medical experiments who were, she recalled, “bones with a little bit of skin.” The experience was too harrowing and Morrison could not endure a complete tour of the camp.

“It’s a privilege to be an American”

After the war, Schendel moved to the United States in 1952 and became a naturalized citizen while Morrison became a nurse. On multiple occasions during their remarks they noted how fortunate they are to be American citizens and urged the audience to be involved in public discourse and elections. Schendel, when comparing his formative years in Germany to the freedom he has experienced in the United States, said, “It’s a privilege to be an American” and Morrison agreed that America is the greatest country on earth.