To the experts and enthusiasts of early North American history, Ann Little, Ph.D., is perhaps best known for her work as a CSU professor of 21 years and as an award-winning author. But to the viewers who tuned into the July 31 episode of NBC’s “Who Do You Think You Are?”, Little was the expert conveying the tribulations of Elizabeth Clawson, accused of witchcraft in the late 17th century and ancestor to actor Zachary Levi.

First premiering in 2004, “Who Do You Think You Are?”, is a documentary series featuring celebrities tracing their ancestries with the assistance of genealogical and historical experts like Little.

Little’s expertise as a historian of early North America, emphasizing women, gender, and sexuality has made her the go-to expert for the showrunners in delving into the lives of early colonial women. That expertise, on top of two prior appearances on the show (the first being in 2015), made her the obvious choice to lead Levi through the complaint of witchcraft leveled against his ancestor.

But it’s actually the second time Little has guided the show’s featured celebrity through a witchcraft allegation, the first being the 2018 episode featuring Jean Smart discovering her eighth-great-grandmother, Dorcas Galley, was tried for witchcraft in Salem in 1692.

In her latest appearance, Little guided Levi through the charge and eventual acquittal of witchcraft of his tenth-great-grandmother, Elizabeth Clawson of Stamford, Connecticut. Facing persecution at the hands of her neighbors, Clawson was tried in 1692 in Fairfield, Connecticut – the only other state outside of Massachusetts to have an outbreak of witchcraft accusations.

Filmed in January of 2020 in Connecticut, Little gave Levi insight into one of the methods of identifying witches who were accused of witchcraft known as ducking, while the two were seated inside the Fairfield Museum & History Center, but near what remains of the pond suspected of Clawson’s ducking.

“…they bound her and put her in the water to determine whether or not she was a witch. This was an actual practice, right?” Levi asked, “Why would they think that a witch would float but somebody else wouldn’t?”

“This is what’s called ducking the witch or swimming the witch. The belief was that a witch would not sink and drown, but that she would float” Little explained to a shocked Levi, “It had to do with belief in the baptismal qualities of water, that water is a pure element…and a good-hearted Christian would sink.”

Read on for more insights from Little’s experience on the show, her explanation of the ‘witches’ teat’ as part of witchcraft accusations, how to piece together ancestral history, and what we can expect from her upcoming book “Natural Women; Nature, Maternity, And Liberty After the Revolution”.

You were first featured on Who Do You Think You Are in 2015, why did you agree to be featured then?

I think that any time somebody is interested in the specialized knowledge I have, I have an obligation to share it with the public. And I’m also excited by the opportunity to share the knowledge that I have with the public.

In the first, “Who Do You Think You Are?” I did with Tom Bergeron. They (the producers) were researching his French-Canadian roots, and I’m one of the only Anglophone scholars of French-Canadian women’s history in the world. So, they didn’t have a huge number of people to choose from. But I was very happy to be featured.

And then after they used me once and I proved to be easy to work with and comfortable on camera. I think it made it easier for them to recommend me to other producers for other episodes, like the one with Jean Smart that ran in 2018, and the one that’s going to air this summer.

What is the process for researching and analyzing these documents for the show and discussing them?

The research is entirely done by the researchers who work for the production company, and they only bring in historians and genealogists to kind of tell them the variety of stories that they could tell with the material they’re presenting. My job in all of these was to sort of tell them what I saw in the documents.

They would bring the documents to me, I tell them what I see in the documents and what I think is interesting and potentially significant about the family members or the celebrities in question, then and then they take it from there. They decide what is the story going to be, and then when they bring me on camera, I talk about sort of the storyline that we’ve kind of agreed on in advance.

But what I like about working with these producers is that they don’t use me to be a pretend kind of expert to tell the story. They want to tell it. They very much collaborate with the scholars in genealogy – they rely on our expertise.

Was there anything interesting in Zachary Levi’s family history that you can talk about in detail?

I wanted to talk about the witch’s teat that is found on his female ancestor who’s accused of witchcraft but acquitted. We find out that she’s accused of witchcraft. She’s convicted, but they don’t carry out the sentence because some judges in the superior court decide that they don’t want to go ahead and execute somebody on the basis of spectral evidence.

As I recall, there was a story that I thought was interesting about his ancestor being inspected for a witch’s teat and for them finding a witch’s teat, which is basically a mole or any kind of mark on a woman’s body that was allegedly proof of her treachery and witchery.

It’s meant to be a place where allegedly Satan or his minions or his demons would suckle on the witch. It’s very much connected to a sense of female embodiment and magic and diabolical collaboration between women and demons. So I thought that was kind of cool, and you don’t always get discussions of the witches’ teat in America.

But what the producers were very interested in was the pond in which his ancestor was ducked. His ancestor was subjected to a very specific gendered kind of torture wherein a woman accused of witchcraft or a woman who was considered to be troublesome, opinionated or talkative, was dumped in a pond to basically sort of force her to confess and or shut her up. Basically a 17th-century form of waterboarding.

What’s exciting or satisfying to you about providing context about this research, to these celebrities on the show?

It’s an opportunity to show people and this is what I like – they actually show the historical documents or copies of the historical documents. They highlight not just the name of the person involved – who’s the ancestor of the person of the celebrity that we’re working with. But it’s also an opportunity for me to talk about sort of the context of the times and to highlight the importance of the lives of everyday people in American history.

These are not shows that typically find that people are descended from the founding fathers right? This is an opportunity to highlight for other Americans and other viewers how important people’s everyday lives are for people who don’t become sort of celebrities in their time and are nevertheless really important and have significant lives and experiences.

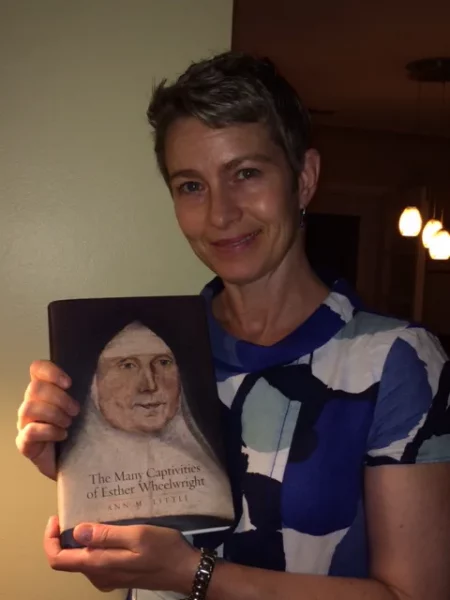

How can those who are interested in learning about their own family history still come up with answers even when they run into these dead ends of no documentation? For example, with your research on Esther Wheelwright for “The Many Captivities of Esther Wheelwright”, there was this time period when she was with the Wabanaki people where there is no documentation. How do you go about trying to piece together that puzzle when it comes to tracing history?

Well, that’s where the work of historians is really important because we can help people find books and articles that will give that kind of larger context. And we can sort of say, “Well, we don’t know for sure this was your ancestor’s experience or not.”

But what we can do is say, “Oh, this is what somebody of that generic age and family structure and sex and race…would have experienced or these would have been things that they might have seen or done in the course of this period in their lives.”

We can kind of use other histories, detailed histories that have been done by other people to sort of fill in those blanks. And you’re very right to sort of mention my book on Esther Wheelwright. That’s the technique, I had to use a great deal of that.

Do you feel you have enough historical context or know about her life enough to understand her perspective? Are you curious about her perspective?

I’m not that curious about what her perspective was. I think her perspective would have been one that is very foreign to me. You know, she became a religious woman and lived in a convent for 71 years of her life. And that is not my perspective.

I think I can guess about what her perspective would have been. But I do have a curiosity about the variety of other experiences as well as hers. In that context, in late 18th century Quebec City, in the late 18th century, and early New England.

You’ve mentioned most people’s family lineages are not going to lead them to the founding fathers. So why is researching and telling the stories of some of these lesser-known historical figures like Esther or even the ‘everyday American’ important?

I wanted to write that book (“The Many Captivities of Esther Wheelwright”) because when I found out about her life, which is truly remarkable especially for a little girl, that she lived in three different cultures and became an insider effectively in all three different major North American cultures: English, French, and Native American. I thought that that was a significant story to tell. But I was also quite frankly, embarrassed to have finished a Ph.D. in early American women’s history, never to have heard about her, never to approach her name mentioned. I started thinking, “Well, which women did I learn about?”.

And moreover, we’re bombarded by biography after biography of founding fathers with glamorous oil paintings on the cover. I thought it was important to tell her story just because there are many early American women’s histories out there. But also, it was a way to kind of diversify our understanding of early American women’s lives, that they don’t all speak English.

They are Protestant, they’re not even necessarily Christian, and she lived as an insider in all three cultures. I thought her story was really a special and important one to commemorate.

You’ve been busy researching for your next book, what can we expect to learn from “Natural Women; Nature, Maternity, And Liberty After the Revolution”

I think we’re going to learn that there’s a lot of environmental history information in women’s diaries and letters that has not been looked at. And I think we’re also going to learn about the powerful continuities in women’s lives. Because, quite frankly of women’s biology, because of the role we play and the unique role we play in sexual reproduction and the caricaturing and education of the young and the nursing.

I should say nursing, as well as nurturing of the young. The book is about the ways in which the generation of women who are born during and after the revolution, the ways in which their lives are different in some ways from their mothers, and their grandmothers’ lives.

Now that you’ve made your third appearance on the show, will we be seeing you on future episodes or other television shows?

Not that I’ve heard of yet, but I’m hopeful that if they need somebody to interpret early American women’s history, they know who they can come to, and I enjoy working with them.

They’re all extremely appreciative of the time I spend, and they’re all very respectful of trying to get the facts straight and trying to sort of tell a responsible story and not just a sensationalistic story.

They really are very devoted to getting the history right in this show. I wouldn’t have worked with them for, you know, three times if that wasn’t the case.

Watch Ann Little in Who Do You Think You Are here.